Readings from and of Palestine (1)

I’m moved to share some recommendations of literature by writers from Palestine, and by those writing of Palestine and of Arab American experience amid the question of Palestine. These are works of poetry, prose, and literary criticism that deserve more readers, more attention.

Literature endures as a site and act of mourning and archive, of radical hope and imagination, of intimate daily life deeply known, of collective vision, dreaming justice. Literature is an alternative present you practice now.

I’m glad to talk more about these books or give you a personal recommendation. I’m grateful to all the writers, readers, translators, & presses who labor to create and document, connect and imagine, in a world whose forms of destruction and erasure are beyond description. The recommendations to follow, which I’ll post in small batches, are not comprehensive and are idiosyncratic to me, their curator. Surely I’ll omit much beautiful urgent work. So this is only one small starting place, offering and gratitude.

Some of these writers and translators have joined us and shared their work in Northeast Ohio. Others, such as Maya Abu Al-Hayyat, are forthcoming here—her novella No One Knows Their Blood Type, translated by Hazem Jamjoum, will be released in English in 2024. Send us a note if you’d like to be kept updated on that, or to propose an event.

—Hilary Plum, h.plum [at] csuohio.edu

YOU CAN BE THE LAST LEAF: SELECTED POEMS

Maya Abu Al-Hayyat

trans. Fady Joudah

Poetry. Milkweed, 2022

I’ve been immersed in the translation of Maya Abu Al-Hayyat’s novella, which we’ll publish next year, and which is so distinct and vital in its feminism, its sense of the body—erotic, dying and birthing, desiring and needy, gross and so tender—and in the author’s humor, which arrives not as a matter of one line or another but a sensibility, a guide, like a hand slipped into the reader’s hand, while history arrives. Al-Hayyat is one of those magical writers who make a poem seem simple. To me those writers live very close to the heart. The heart, meaning not just figuratively, but a bloody and essential organ, insisting on continuing its simple work, something completely strange to the mind and so very materially real. The word “intimate” often appears in responses to her work. A rendering of everyday life under occupation. “The allure of these poems is simple,” Fady Joudah writes in his foreword, “They illuminate the inseparability of private and public domains within a forcibly imposed and constricted, indeed strangled, space.” I read this book over a year ago, in a dark bar in the summer, you had to go downstairs from the sidewalk to get inside, in a city I no longer lived in. I was drinking well gin and tonics slowly and a friend I hadn’t seen in a long time eventually appeared, so that we had years of life to catch up on, which was precious, and yet we also easily could never, by that time and after that gap, have met again. This is just one example of how to read this stunning and very alive work.

A Road for Loss

Like the rest of you

I thought of escape.

But I have a fear of flying,

a phobia of congested bridges

and traffic accidents,

of learning a new language.

My plan’s for a simple getaway,

a small departure:

pack my children in a suitcase

and to a new place we go.

Directions confuse me:

there’s no forest in this city,

no desert either.

Do you know a road for loss

that doesn’t end

in a settlement?

I thought of befriending animals,

the adorable type, as substitutes

for my children’s electronic toys,

but I want a place for getting lost.

My children will grow,

their questions will multiply,

and I don’t tell lies,

but teachers distort my words.

I don’t hold grudges,

but neighbors are always nosy.

I don’t rebuke,

but enemies kill.

My children grow older,

and no one’s thought yet

to broadcast the final news hour,

shut down religious channels,

seal school roofs and walls,

end torture.

I don’t dare to speak.

Whatever I speak of happens.

I don’t want to speak.

I’d rather be lost.

QUIET ORIENT RIOT

Nathalie Khankan

Poetry. Omnidawn, 2020

From a review at Cleveland Review of Books:

“my ovaries have been in the hands of men on both sides,” Nathalie Khankan writes in this extraordinary debut, which depicts the experience of conceiving a Palestinian child using Israeli assisted reproductive technology. In everyday, understated language, Khankan precisely renders the paradoxes of empire, technology, and survival that define this experience. …

In an interview, Khankan describes her children as “Palestinian children born on Palestinian soil but they can’t be recognized as such.” The details of her family’s situation, visa status, profession, and backgrounds (they lived in Ramallah for eight years and “didn’t leave willingly,” she reports in that same interview, from her current home in San Francisco; she herself was born in Denmark, her parents Finnish and Syrian) mostly don’t appear here. Rather the book attests to the possibility, goodness, justice, and fruitfulness of daily living in Palestine, life known as Palestinian. Poetry may be a means to address a collective historical violence—Israel’s military occupation of Palestinian territory—using only and always the small personal technology of a thinking, reproducing, caring, writing body. “human beings are plenty | hostile the turnstiles | soon i’ll break into a fact on the ground,” one poem expresses, calling up the checkpoints and settlements that dominate Palestinian landscapes and life, as refracted through the lone fact of the self, vulnerable witness, contingent agent.

quiet orient riot offers the everyday thinking of an unthinkable situation. … [more here]

ADRENALIN

Ghayath Almadhoun

trans. Catherine Cobham

Poetry. Action Books, 2017

From a review in Poetry Northwest:

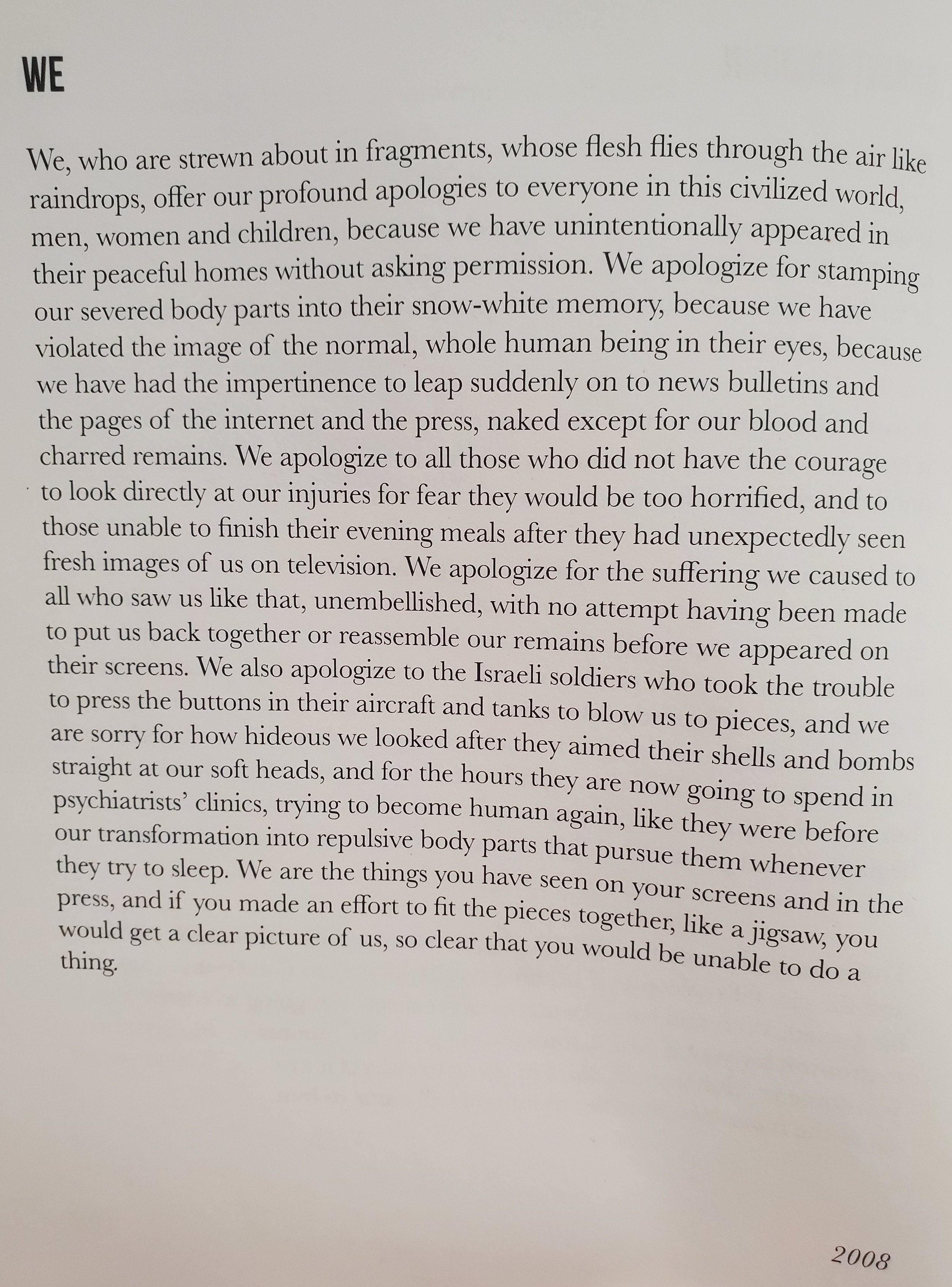

Ghayath Almadhoun’s Adrenalin is about living and dying in cities. I say “about” meaning not just the subjects with which the book is concerned—the cities of Damascus and Stockholm—but that the book circles or nears these cities, moves about them, approaches and reverses direction (about face). No matter your direction somehow the city defines your movements, a city at once here and beyond you. Almadhoun is, his bio tells us, “a Palestinian poet who was born in a refugee camp in Damascus in 1979”; “[he] has lived in Stockholm since 2008.” Adrenalin is his first appearance in English, in Catherine Cobham’s translation. This book maps the distance between these two cities: the violence that distance allows, the violence through which that distance is maintained, and how the poet’s own body may breach it: “I’ve cleaned my room of any trace of death / so that you don’t feel when I invite you for a glass of wine / that despite the fact I’m in Stockholm / I’m still in Damascus.”

The distance between the European cities to which in recent years refugees flee and the cities from which they are fleeing is marked by the infinitely violent history of colonialism. … For some, war takes place on a screen or in a far colony, obscured by gem or game; for others, in the bullet that finds them: “I was exploring the difference between revolution and war when a bullet passed through my body…” (“The Details”). … [more here]