INNOCENCE: An Interview with Michael Joseph Walsh

Michael Joseph Walsh’s debut poetry collection, Innocence, was selected by Shane McCrae as the winner of the CSU Poetry Center’s 2021 Lighthouse Poetry Series Competition. Of Innocence, McCrae remarks: “Complete as first books of poetry rarely are, integral as first books of poetry rarely are, Innocence reads as if it exists only to be; it pursues no end other than its own being, which is the end of all successful works of art, whatever a particular work’s subject.” The Poetry Center’s Joee Goheen spoke with Walsh about the processes of accretion, relation, and sustained work that resulted in this stunning first book.

Innocence feels incredibly profound—when I recently introduced you at the Lighthouse reading, I described your book as “a push from consciousness, from the high tower of self, and a slow, swirling fall into a gradient of reality and possibility. Of life lived and seen through the Eye that is us all. A descent from disambiguation…” I feel very much that Innocence is tracing the outline of something that keeps changing shape and thus has a wealth or multitude of meaning. Could you describe your writing process and how these poems take shape?

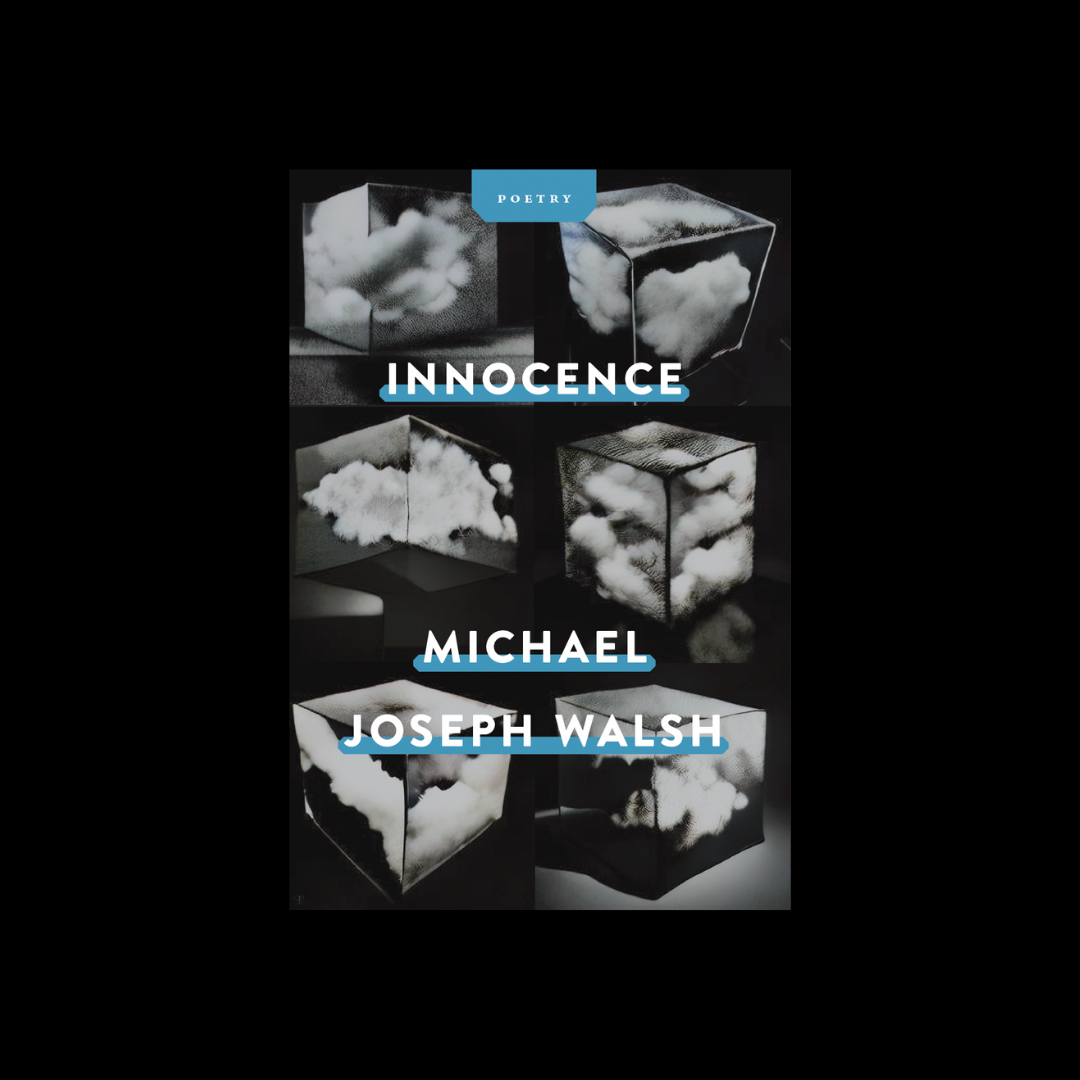

I like the words you’ve chosen here: “push,” “fall,” “descent.” Others have described their experiences of the poems in terms of suspension, which I think is also apt. In hindsight, I think one of the book’s central images is a/the cloud, another floating thing, albeit not one that we think of as moving vertically, which I think you’re right that the poems in this book tend to do (both up and down).

I do think that I like my poems to be always, or almost always, between things—either falling from some limit (and toward another), or rising back up into it. One thing that has always drawn me to poetry is how well-suited it is to engaging with limits and event horizons. Although we can never get beyond them (which would be impossible, if the limits are real ones), I think a poem can give us a sense, through its failure to do the impossible, of the empty vastness that lies beyond those limits, a vastness to which we will never have access and which, by virtue of that, is inexhaustibly seductive.

My writing process is improvisational, but also accretive. I write quickly, but I discard a lot, and I finish things slowly; there’s a lot of cutting and re-arranging involved. For that reason I’ve always found collage and assemblage to be a great source of inspiration, at least as a model or metaphor for what I’m doing. One thing I try not to do is to let my critical intelligence get involved in the process too early. When I was starting out in poetry, I thought every move in a poem had to be deliberate—otherwise it was cheating. Maybe some people can work that way—Poe at least pretended to—but it didn’t work for me. “You just go on your nerve,” as O’Hara put it, is good advice, with the caveat that at some point the “just” needs to be set aside (and that your “nerve” can be developed—it isn’t simply given). I want my poems to be largely mysterious to me; that estrangement gives them a charge (in my eyes) that they wouldn’t otherwise have. I know I wrote them, but I like them best when they feel like they were written by someone else, even if that someone else is an “other” (“J’est un autre”) who’s very much me, or even more me than me.

In your interview with poetry mini interviews, you talk about poetry having a certain density that allows it to accomplish things more readily than other forms. This density of meaning is certainly present in Innocence—would you be willing to talk about what you feel the book and the individual poems within accomplish? What are some of the “bodies inside experience” this book pursues?

One thing I specifically look to poetry for—and I think this is related to what I said above about limits—is the provision of experiences—cognitive, affective, narrative—that are 1) either impossible in “the real world,” but possible in language by virtue of its inherent abstraction and (spooky) virtuality, or 2) possible in the real world but almost impossibly heightened through the technique (the technology) of poetry (e.g., the splash of Basho’s frog). I guess that’s another way of saying that what I want from poetry is a kind of transcendence, granting that there are many flavors of transcendence, and many ways of achieving it (including by aiming at immanence). Whether my poems ever accomplish this is up to the judgment of the reader, but I do think it’s what I’m targeting. I want the feeling of being taken out of myself, both in the writing and the reading.

You (or rather I) mentioned density. Density is one way of thinking about it, but at their limits things tend to flip into their opposites. The flipside of density is a kind of nebulosity (“cloud-like-ness”), as the too-much-ness of density produces a feeling of bewilderment. I called the book Innocence because the poem “Innocence” felt like the title poem, and I titled that poem “Innocence” simply because the word “innocence” (In the lines “A volcano of oil is flowing, / and we believe in it, / and call it our innocence”) jumped out at me. But after the fact, I noticed some connections that I hadn’t been consciously aware of while writing the book. For one, “Innocence” is one English translation of 无妄, the 25th hexagram of the Yijing, whose name can also be translated as something like “without guile,” and which is associated with “the unexpected.” Thinking about this hexagram (and its associated image: “Under heaven thunder rolls”) prompted me to think more deeply about the prominence of cloud images in the book. And from there I was reminded of the Cloud of Unknowing, and then of one of my favorite Zen koans, in which the bodhisattva Dizang says “不知最親切”—“Not knowing is most intimate.” So “Innocence” for me is tied to “not knowing,” and also to intimacy, broadly construed. One approaches a thing that seems solid from a distance, then finds oneself lost inside of it, in the body of a cloud.

In that same vein, one of the book’s concerns is “the future,” which is always unknowable but now seems especially so. In the face of this one feels a sense of dread, but also a sense of giddiness, as all that seemed solid comes to seem nebulous, while the associated dangers remain frighteningly real.

You’re Korean American and a few of your poems appear in both English and Korean. I love the forms “Pure Land,” “Playground,” and “Native Country” take and their sestina-like repetition, as well as the experience of seeing the Hangul next to the English. What was this process of translation like and what might you (or did you) discover along the way?

At the time I was working on improving my vocabulary in Korean. I’d collected a lot of sentences, mostly taken from grammar books and online dictionaries, which I would then review at random. Eventually I got the idea that I should “do something” with those sentences, but I didn’t yet know what form that would take.

The real impetus was my reading of John Yau’s Bijoux in the Dark, which includes a number of poems that use basically this form. I think what attracted me to them was their simplicity—each line is an end-stopped sentence, and each line repeats exactly once. And I liked the way they foreground the sentence as a unit, giving each sentence its due and allowing it a reincarnation in which nothing about it has changed, other than its context and the fact that we still remember its previous life. The sentences repeat, but you can’t step in the same sentence twice. The juxtapositions that Yau achieves using this form reminded me of what it was like to review the sentences I’d collected, and I went from there

To a certain extent I was also drawn to the idea of attempting to “write” poems in Korean. Doing so in the usual way was and is beyond what I can do—I haven’t lived in Korea in many years, so at this point I’m much better at understanding the language than producing it—but working through collage made things more approachable. Most of the lines are lightly edited, and many are spliced together from two or more unrelated sentences.

In hindsight, I also think the “doubleness” of the poems—both in terms of their internal structure and the fact that the English and Korean versions are paired—in some sense “mirrors” my position as a half-Korean Korean-American. There’s probably also an element of wish fulfillment at play. In each pair of poems, Korean and English are given precisely equal place. I think there’s a part of me that wishes that were the case, that Korean and English—in terms of both language and culture—were similarly equal for me, even though I know that, realistically speaking, that will never happen.

Are you working on anything now?/What’s next?!

Good question! Since finishing the poems in this book I’ve gone through a long period of writing without finishing anything. But I’ve generated some material, so I’m hoping some of those seeds bear fruit this year. I’ve also been (very slowly) working on some translation projects, including poems and essays by Yi Sang, some of which should be appearing soon. And I’ll be putting out a new issue of APARTMENT in the next few weeks, which I’m excited about.

So, despite feeling between things, which I think is normal after finishing a book, I’m doing my best to stay busy. My friend Elisa Gabbert keeps a Post-It note above her desk that reads, in all caps, JUST DO YOUR WORK. I haven’t created my own note, but I do think about hers often, the way I think about Rodin’s famous advice to Rilke (“Il faut toujours travailler”). In that sense the note is in my head, if not above my desk. Art is a discipline, if only in the sense that you have to show up, and showing up—despite everything that conspires against it—is half the battle, and maybe even more than that. So I guess, in a larger sense, that’s what I’m working on at the moment: figuring out how I can arrange my life so that I can keep showing up, and doing my work.

Michael Joseph Walsh is a Korean American poet and the editor of APARTMENT Poetry. He lives in Denver.

Joee Goheen Joee Goheen is a writer from West Virginia in her third year of the NEOMFA.