AND COULD THEY HEAR ME I WOULD TELL THEM (AJA COUCHOIS DUNCAN)

Bio: Aja Couchois Duncan is a two spirit, social justice coach and capacity builder of Ojibwe, French and Scottish descent who lives on the ancestral and stolen land of the Coast Miwok people. Her debut collection, Restless Continent (Litmus Press, 2016) was selected by Entropy Magazine as one of the best poetry collections of 2016 and awarded the California Book Award for Poetry in 2017. In 2020, Sweet Land—a collaborative opera project which brought together composers Raven Chacon and Du Yun, librettists Aja Couchois Duncan and Douglas Kearney, and co-directors Cannupa Hanska Luger and Yuval Sharon—was produced in the Los Angeles State Historic Park to critical acclaim and named the Best Opera of 2020 by the Music Critics Association of North America. Her latest book, Vestigial was published by Litmus Press in 2021. When not writing or working, Aja can be found running the west Marin hills with her Australian Cattle Dog Dublin, training with horses, or weaving small pine needle baskets. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from San Francisco State University and a variety of other degrees and credentials to certify her as human. Great Spirit knew it all along.

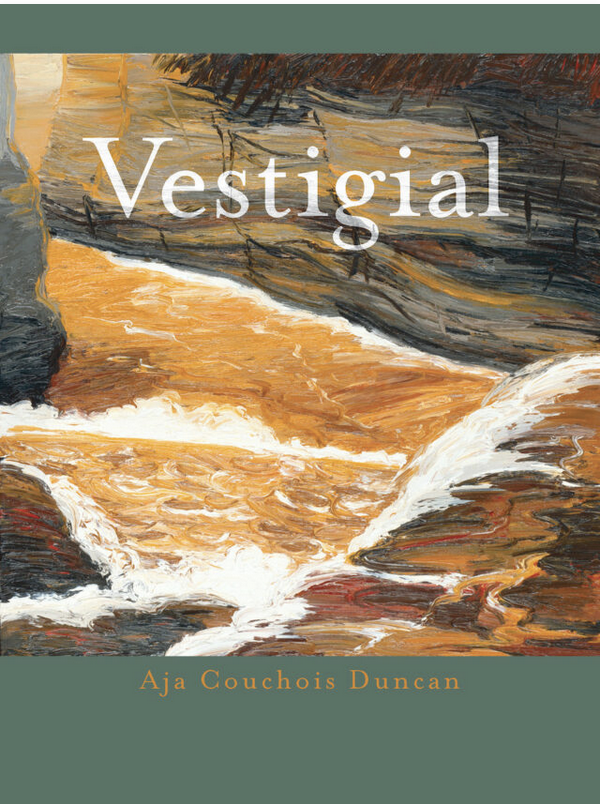

Book Title: Vestigial

Press: Litmus Press

1. What is something that surprised you during the writing, editing, or publishing process for Vestigial?

So much was a surprise. The book was shaped, carved away, then reshaped. I followed it and let it show me what it wanted to be. It started with insects and evolution, then became a love story, then a story of climate catastrophe, and eventually became a multilayered and tightly woven lyric novel composed of all three.

2. How might you describe the “experiment” or challenge of this book? What form, procedure, sound, or mystery enlivened your mind while writing?

I think the experiment was really in trusting myself and my writing practice—which exists both within and beyond me—that all the different tributaries would eventually flow into the river that is this book. The book begins before it began and ends long after the final page. Tributaries, rivers, oceans, clouds, and rain falling into eddies and streams only to begin again. The book needed this sense of time, both geologic and corporeal, which meant I needed to give it this time as well. It truly took years.

When it also took years to publish, I worried that aspects of the book that were, at the time I wrote them, somewhat apocryphal descriptions about climate change and climate disasters would seem passé even trite in our current context. Perhaps they do. When I wrote Vestigial, I was listening to the future. But the future is the present too.

3. Can you discuss an edit, idea, response, or interaction with another person that helped this book find its way in the world—aesthetically, materially, visually, structurally, spiritually…?

I grew up believing my name meant hawk. I no longer know if this is true. But raptors have always figured largely in my life. So both spiritually and aesthetically, birds and sky, giizhig and binesi, helped birth this book.

The book is dedicated to a few people, one is the ex who made writing it so necessary. Another is an amazing writer and friend, Stacy Nathaniel Jackson, who read so many iterations of Vestigial and challenged me to revise it until the stories wove together. Stacy’s debut novel, The Ephemera Collector is forthcoming next year from Liveright. I highly recommend it.

One novel I read while writing Vestigial that took my breath away was The Reason for Crows by Diane Glancy who is also a poet. There is not much of a relationship between the two books in terms of structure or narrative trajectories. But they both evoke a sense of compression and are very sensorial. So I know Vestigial was made possible in some ways by Diane Glancy’s work. And also, thinking of poets’ novels, I should name Autobiography of Red by Anne Carson. This book thrilled me when I first read it a decade before writing Vestigial. It thrills me still.

4. Is there a physical place or space you associate with the poems in Vestigial?

There are many places I associate with Vestigial. Water, sky, a bird cage. Aki, her exteriors and interiors. Caves and fire and meteor depressions. By mainly I associate it with a yard and a tree and a bear and a boat.

5. What’s something that feels difficult about having a book—or this book, specifically—come into the world?

There are many things challenging about having Vestigial in the world. One is that a significant tributary of the book is drawn from a very dramatic, even traumatic, relationship I was in on and off for many years.

The other challenge is that I am talking about gender and sex transition in ways that reflect an experience in all its complexity. Writing is by its very nature an act of vulnerability, but this book required me to let go of the writer—to let go of my ego and all the worries it has about how people read me through my words—and simply let the aadizookaan emerge.

6. What do you appreciate about the press (Litmus Press) that published this work?

I am so appreciative of Litmus Press. They have published the only two books I have in print. And they publish incredibly complex, inspiring, challenging, inventive work. When I did a small book tour for Restless Continent, I got to read with Youmna Chala whose book Paper Camera (published by Litmus) is absolutely amazing. Everyone must read it. They also are now tending The Post-Appollo Press, which has been publishing really important writers for decades. I have read and reread Etel Adnan and her extraordinary work for more than twenty years.

Working with Litmus on Vestigial was an amazing experience. There was so much editorial support. Thank god for editors. We are such better writers because of them. Litmus also published a teaching guide for my work. It was a lovely to collaborate a bit on that project with them. Small press publishing is such a labor of love; they care about getting complex, boundary shifting writing out into the world and we come together as a community of writers, editors and publishers (most of who are also writers) and give our time and livelihood to make small press books possible.

7. Do you recall the most recent small press (micro, indie, DIY, university) publication you’ve recommended? What made you want to tell someone about it?

I absolutely loved Shapes of Native Nonfiction: Collected Essays by Contemporary Writers, edited by Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warbuton (published by University of Washington Press). The collection troubles so many categories: who’s Native, what it means to tell Native stories, what’s fiction and nonfiction, who and what essays talk to and about. In so doing it juxtaposes Western and Native ways of living and being that are funny, distressing, and utterly queer—in all the meanings of that word.

Wave Books has been publishing beautiful work. The most recent book by my friend Renee Gladman, Plans for Sentences, is particularly spectacular. In it she is drawing sentences and writing toward their variegated extremities, the amputations and distended limbs.

Julian Mithra’s debut collection, Unearthingly (published by KERNPUNKT Press) engages a dizzying array of literary forms to construct a poetic documentation of violence, nationalism, environmental devastation, and the strange, but unstoppable arc of girlhood.

It is the nature of lists that things are left out, forgotten, missing.

8. Is there a text, song, piece of art, or made thing that your book talks to, borrows from, fights with, or is in tribute to?

When I give talks/readings about Restless Continent and Vestigial, I often share an image from Ojibwe artist Carl Beam titled Only Poetry Remains. He was the first Native person to have his work purchased by the National Gallery of Canada as contemporary art.

I believe the text reads: “The Whale Of Our World … Only Poetry Remains.”

I do not know how exactly I am in conversation with this piece—as it is both the art itself and its historical legacy that activates me—I only know that I am. Or this art is in conversation with me.

9. What adventures are you looking forward to, thinking about, or practicing now?

In terms of literary adventures, I am working on multiple manuscripts. This summer I have been writing a collection of short shorts or sudden fiction. The form matches my attention span during the summer when all I want to do is swim, dance or run. As we move into fall and winter, I will turn back to Wild Kin, which I started early in the pandemic and is similar to Vestigial in that I think of it as a lyric novel. Beyond writing, I will be starting a yoga teacher training program in the beginning of the new year to deepen my yoga and meditation practice. I have also been learning to surf, specifically surfing off the southern tip of Point Reyes, which thrills and terrifies me as the ocean here is home to large marine predators.

10. Who will you gift a copy of Vestigial to? Or where will you leave it for someone to find?

I would leave Vestigial in a glass box on the wooden seat of an abandoned boat in the inter coastal waterways of the San Francisco Bay. May she lay there years undiscovered. And then one day, someone, perhaps a fox or oshkiniigikwe, will find her and the words inside will make her feel connected to something beyond her visual field, beyond the beat of her own percussive heart.